![cover Kumarasambhava - Kale]() KALIDASA, (kaalidaasa), India’s greatest Sanskrit poet and dramatist. In spite of the celebrity of his name, the time when he flourished always has been an unsettled question, although most scholars nowadays favor the middle of the 4th and early 5th centuries A.D., during the reigns of Chandragupta II Vikramaaditya and his successor Kumaaragupta. Undetermined also is the place of Kaalidaasa’s principal literary activity, as the frequent and minute geographic allusions in his works suggest that he traveled extensively.

KALIDASA, (kaalidaasa), India’s greatest Sanskrit poet and dramatist. In spite of the celebrity of his name, the time when he flourished always has been an unsettled question, although most scholars nowadays favor the middle of the 4th and early 5th centuries A.D., during the reigns of Chandragupta II Vikramaaditya and his successor Kumaaragupta. Undetermined also is the place of Kaalidaasa’s principal literary activity, as the frequent and minute geographic allusions in his works suggest that he traveled extensively.

Numerous works have been attributed to his authorship. Most of them, however, are either by lesser poets bearing the same name or by others of some intrinsic worth, whose works simply chanced to be associated with Kaalidaasa’s name their own names having long before ceased to be remembered. Only seven are generally considered genuine.

Kalidasa’s Life Time: There are eight hypothesis about his lifetime. The main logics, ecidences are as follows:

1. 6th century AD, Yashodharman defeated Mihirkul of HooN clan. Dr. Harnely says this Yashodharman is kalidas’s Vikramaaditya. Flaw: Y. never tok the title of Vikramaaditya

2. Fargusen says that 6th century AD, there was a king Vikramaaditya in Ujjayini (present day Ujjain). he defeated Shakas, started `Vikram-samvat’ calendar, starting it 600 years back 57BC. Prof. Max Muller basing on this said that Kalidasa was in the court of this Vikram. Flaw: There was no king by name VIkramaaditya in 600 AD in India. `Vikram-samvat’ calendar was in vogue since 1st century BC as `maalav-samvat’. This is clear from `mandasor’ `shilaalekha’ (stone writings) of VatsabhaTTi.

3. Kalidasa was familiar with Greek astronomy, using words like `jaamitra’. Greek astronomy/geometry was popularised by AryabhaTTa who was in 5th century AD. SO, Kalidasa was in 6th AD onwards. Dr McDonald refutes this saying `Romaka-siddhaanta’ was prevalant before AryabhaTTa, so he didn’t popularise Greek astronomy.

4. Mallinaath (the most famous commentrator on Kalidasa) gives two meanings to Meghadoot’s 14th verse. He says that `dinnaaga’ and `nichula’ words refer to Buddhist philosophers `dinnaaga’. Based on this some scholars put kalidasa in 6th century AD `coz kalidasa’s contemporary `dinnaaga’ was disciple of Vasubandhu who was in 6th century AD. Flaw: Vasubandhu was apparently in 400 AD `coz his books were translated in Chinese around 475-525 AD.

Finally this is what can be said about his lifetime: Kalidasa in his drama `Malvikaa-agni-mitra’ makes Agni-mitra his hero, who was the son of Pushamitra Shunga who was in 2nd century BC. This is his upper bound. Banabhatta in the preface of his Kadambari mentions Kalidasa. Banabhatta was in early 7th century AD. This is Kalidasa’s lower bound.

Kalidasa’s Life: Many tell tales are there for his life. Some call him native of Kashmir, some of Vidarbh, some of Bengal and others of Ujjain. It is said that he was a dumb fool to start with. The king’s daughter was a very learned lady and said that she will marry him who will defeat her in `shaastraartha’ (debate on the scriptures). Anyone who gets defeated will be black faced, head shaven and kicked out of country on a donkey. (The punishment part might be later aditions!) SO, the pundits took Kalidasa (whom they apparently saw cutting the tree branch on which he was sitting) for debate. They said that he (Kalidasa) only does mute debates. The princess showed him one finger saying `shakti is one’. He thot she will poke his one eye, so he showed her two fingers. She accepted it as valid answer, since `shakti’ is manifest in duality (shiv-shakti, nar-naaree etc etc). She showed her the palm with fingers extended like in a slap. He showed her the fist. She accepted it as answer to her question. She said `five elements’ and he said `make the body’ (earth, water, fire, air, and void). [ The debate explanations are also apparently later additions] So they get married and she finds he is a dumbo. So she kicks him out of the house. He straightaway went to Kali’s temple and cut his tongue at her feet. Kali was appeased with him and granted him profound wisdom. When he returned to his house, his wife (the learned) asked, “asti kashchit vaag-visheshaH” (asti = is; kashchit = when, as in questioning; vaag = speech, visheshaH = expert; i.e. “are you now an expert in speaking”).

And the great Kalidasa wrote three books starting with the 3 words:

with asti = asti-uttarasyaam dishi = Kumara-sambhavam (epic)

with kashchit = kashchit-kaantaa = Meghdoot (poetry)

with vaag = vaagarthaaviva = Raghuvansha (epic)

Another story says that he was the friend of Kumardas of Ceylon. He was killed by a courtesan once when he visited his friend in Ceylon.

(Courtesy: Shashikanth Joshi)

Works of Kalidasa:

Plays – There are three plays, the earliest of which is probably the Malavikaagnimitra ( Malavikaa and Agnimitra), a work concerned with palace intrigue. It is of special interest because the hero is a historical figure, King Agnimitra, whose father, Pushhpamitra, wrested the kingship of northern India from the Mauryan king Brihadratha about 185 B.C. and established the Sunga dvnasty, which held power for more than a century. The Vikramorvashiiya ( Urvashii Won Through Valor) is based on the old legend of the love of the mortal Pururavaas for the heavenly damsel Urvashii. The legend occurs in embryonic form in a hymn of the Rig Veda and in a much amplified version in the ShatapathabraahmaNa.

The third play, AbhiGYaanashaakuntala ( Shakuntalaa Recognized by the Token Ring), is the work by which Kaalidaasa is best known not only in India but throughout the world. It was the first work of Kaalidaasa to be translated into English from which was made a German translation in 1791 that evoked the often quoted admiration by Goethe. The raw material for this play, which usually is called in English simply Shaakuntala after the name of the heroine, is contained in the Mahaabhaarata and in similar form also in the PadmapuraaNa, but these versions seem crude and primitive when compared with Kaalidaasa’s polished and refined treatment of the story. In bare outline the story of the play is as follows: King Dushhyanta, while on a hunting expedition, meets the hermit-girl Shakuntalaa, whom he marries in the hermitage by a ceremony of mutual consent. Obliged by affairs of state to return to his palace, he gives Shakuntalaa his signet ring, promising to send for her later. But when Shakuntalaa comes to the court for their reunion, pregnant with his child, Dushhyanta fails to acknowledge her as his wife because of a curse. The spell is subsequently broken by the discovery of the ring, which Shakuntalaa had lost on her way to the court. The couple are later reunited, and all ends happily.

The influence of the AbhiGYaanashaakuntala outside India is evident not only in the abundance of translations in many languages, but also in its adaptation to the operatic stage by Paderewski, Weinggartner, and Alfano.

Poems – In addition to these three plays Kalidaaa wrote two long epic poems, the Kumarasambhava ( Birth of Kumara) and the Raghuvamsha ( Dynasty of Raghu). The former is concerned with the events that lead to the marriage of the god Shiva and Paarvatii, daughter of the Himalayas. This union was desired by the gods for the production of a son, Kumara, god of war, who would help them defeat the demon Taraka. The gods induce Kama, god of love, to discharge an amatory arrow at Siva who is engrossed in meditation. Angered by this interruption of his austerities, he burns Kama to ashes with a glance of his third eye. But love for Paarvatii has been aroused, and it culminates in their marriage.

The Raghuvamsha treats of the family to which the great hero Rama belonged, commencing with its earliest antecedents and encapsulating the principal events told in the Raamaayana of Valmiki. But like the Kumarasambhava, the last nine cantos of which are clearly the addition of another poet, the Raghuvamsha ends rather abruptly, suggesting either that it was left unfinished by the poet or that its final portion was lost early.

Finally there are two lyric poems, the Meghaduta ( Cloud Messenger) and the Ritusamhara ( Description of the Seasons). The latter, if at all a genuine work of Kalidasa, must surely be regarded as a youthful composition, as it is distinguished by rather exaggerated and overly exuberant depictions of nature, such as are not elsewhere typical of the poet. It is of tangential interest, however, that the Ritusamhara, published in Bengal in 1792, was the first book to be printed in Sanskrit.

On the other hand, the Meghaduta, until the 1960’s hardly known outside India, is in many ways the finest and most perfect of all Kalidasa’s works and certainly one of the masterpiece of world literature. A short poem of 111 stanzas, it is founded at once upon the barest and yet most original of plots. For some unexplained dereliction of duty, a Yaksha, or attendant of Kubera, god of wealth, has been sent by his lord into yearlong exile in the mountains of central India, far away from his beloved wife on Mount Kaildasa in the Himalayas. At the opening of the poem, particularly distraught and hapless at the onset of the rains when the sky is dark and gloomy with clouds, the yaksa opens his heart to a cloud hugging close the mountain top. He requests it mere aggregation of smoke, lightning, water, and wind that it is, to convey a message of consolation to his beloved while on its northward course. The Yaksha then describes the many captivating sights that are in store for the cloud on its way to the fabulous city of Alakaa, where his wife languishes amid her memories of him. Throughout the Meghaduta, as perhaps nowhere else So plentifully in Kalidasa’s works, are an unvarying freshness of inspiration and charm, delight imagery and fancy, profound insight into the emotions, and a oneness with the phenomena of nature. Moreover, the fluidity and beauty of the language are probably unmatched in Sanskrit literature, a feature all the more remarkable for its inevitable loss in translation.

(Courtesy: Walter Harding Maurer University of Hawaii at Manoe)

DOWNLOAD LINKS TO COMPLETE WORKS OF KALIDASA

1. Abhijnana Sakuntalam

Abhijnana Sakuntalam Of Kalidasa – M. R.Kale

Abhijnana Sakuntalam English Translation by CSR Sastri

Sakuntala – Sanskrit Text with English Translation by Monier Williams

Sakuntala – English Translation by JG Jennings

Kalidasa’s Sakuntala – English Translation by Richard Pischel

2. Malavikagnimitram

Malavikagnimitram of Kalidasa – Skt Commentary – KP Parab

Malavikagnimitram English Translation by CH Tawney

3. Vikramorvasiyam

Vikramorvasiyam Sanksirt Text with English Notes by SP Pandit

Vikramorvasiyam English Translation by EB Cowell

4. Kumarasambhavam

Kumarasambhava Cantos I-VII – Sanskrit Commentary, English Translation & Notes – MR Kale

Kumarasambhavam – Eng Translation by RTH Griffith

Kumarasambhavam with Mallinatha’s Sanskrit Commentary

5. Raghuvamsam

Raghuvamsa with Mallinatha’s commentary Hindi translation by Pt. Lakshmi Prapanna Acharya(DJVU)

Raghuvamsa with Mallinatha’s commentary Shankar Pandit Part 3

Raghuvamsa English Translation by De Lacy Johnston

Cantos 1 to 10 with Mallinatha’s commentary and Eng Translation by MR Kale

Raghuvamsa with Hindi Tika by Jvalaprasa Mishra

Raghuvamsa with Commentary of Mallinatha & English Translation by GR Nandargikar

6. Meghasandesam (Meghadutam)

Meghasandesa with Dakshinavartanatha’s Tika – TG Sastri

Meghaduta with Sanjivani Vyakhya 1894

Kalidasa’s Meghaduta with Skt Commentary & English Translation – KB Pathak, 1916

Meghaduta English Translation by HH Wilson, 1814

Meghaduta English Translation by Col. HA Ouvry, 1868

7. Works of Kalidasa

Works of Kalidasa English Translation – William Jones 1901

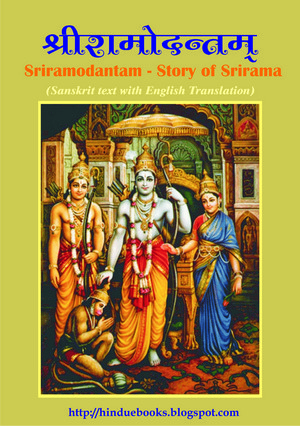

The term Sriramodantam is composed of two words ‘Srirama’ and ‘udantam’ meaning ‘the story of Srirama’. Sriramodantam is a ‘laghukavyam’ (minor poetical composition) that has been in use as the first text in old Sanskrit Curriculum of Kerala for last five centuries. As per this curriculum the students were taught this text along with Amarakosa and Siddharoopam immediately after they had learnt the Sanskrit alphabets (Varnamala). This Kavya, which is a highly abridged version of “Valmiki Ramayana”, was used as a tool to teach effectively Vibhakti, Sandhi, Samasa, etc to young pupils.

The term Sriramodantam is composed of two words ‘Srirama’ and ‘udantam’ meaning ‘the story of Srirama’. Sriramodantam is a ‘laghukavyam’ (minor poetical composition) that has been in use as the first text in old Sanskrit Curriculum of Kerala for last five centuries. As per this curriculum the students were taught this text along with Amarakosa and Siddharoopam immediately after they had learnt the Sanskrit alphabets (Varnamala). This Kavya, which is a highly abridged version of “Valmiki Ramayana”, was used as a tool to teach effectively Vibhakti, Sandhi, Samasa, etc to young pupils.